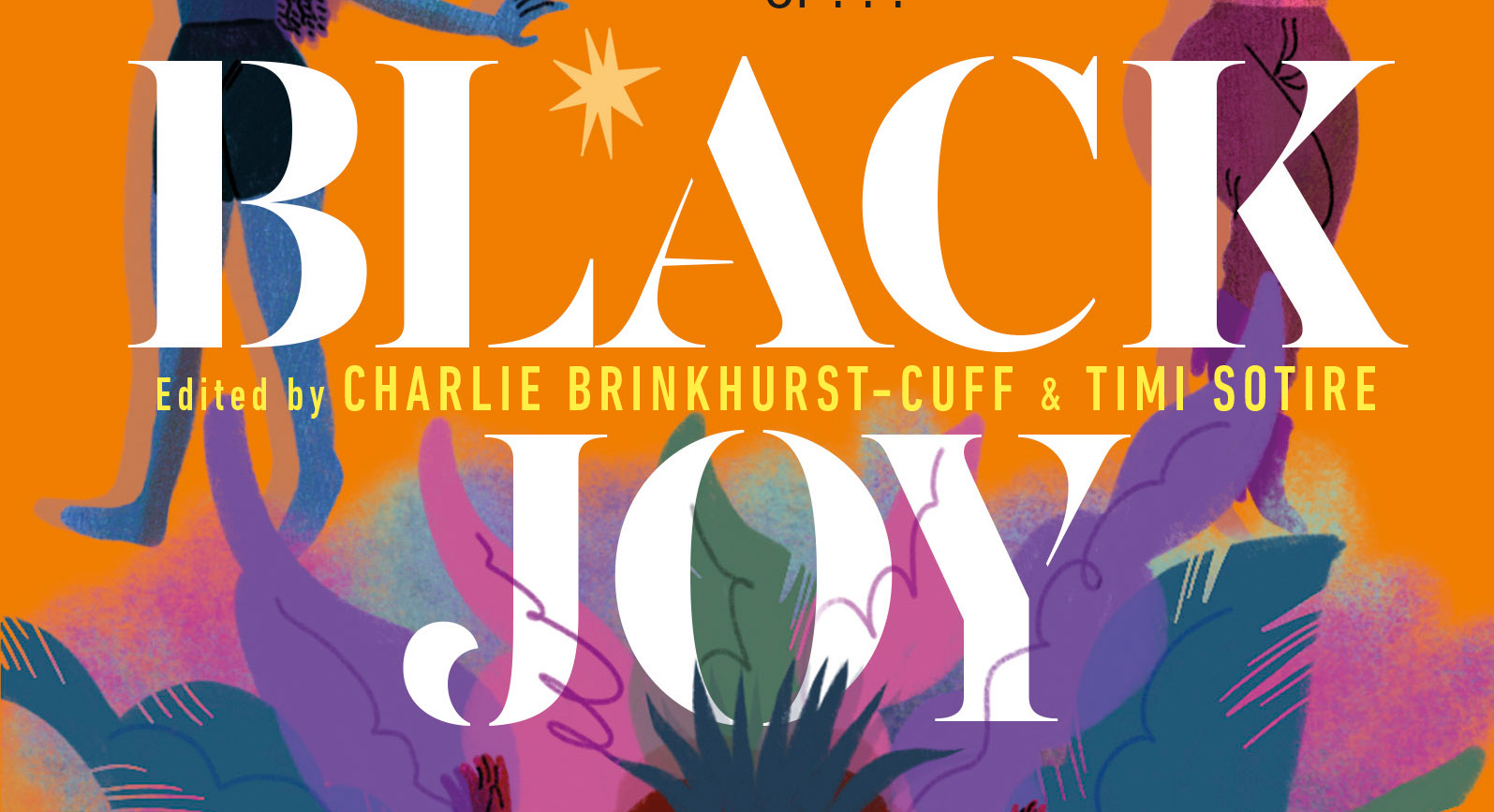

The Tea Is That There's Joy in Blackness: Black Joy

Journalists Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff and Timi Sotire unpack why we need narratives that share delight in being Black in Black Joy, an anthology sparking light from twenty-nine Black British writers.

Interview by Tsholofelo Lehaha

There has been a wave of spectacular receptions since Penguin Books announced the release of Black Joy, an anthology packed with unbelievably gifted Black British minds - such as trans nonbinary scholar, Melz Owusu the satirical, provoking writing of Munya Chawawa, and radio presenter Richie Brave.

The collection expertly edited by Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff and Timi Sotire comes at a time where we have seen the need to provide new examples of blackness in culture as a whole.

In almost every movie or book featuring a Black British protagonist, the protagonist is always tied to a victorious moment after experiencing and overcoming some particular black trauma. This has been a notorious trend that turned generic for years, so it was with welcome that we have seen the arrival of literature that does not require black pain and suffering in order to gauge interest.

This anthology verifies the expression of joy and disables the progression of shoehorning that comes from the ongoing norms around blackness and tragedy. The book pins joy from music, memory, sisterhood, sexuality, and a lot more that these writers found to be what defines that for them.

“Black joy in this climate is an undoubtedly political reaction to the world we are living in, but we must be careful to push the conversation beyond this moment, and beyond a hashtag,” the multi-award-winning journalist, Charlie explains.

It is autumn in London when Charlie pops up on the screen over Zoom. She’s warm, snuggled in a throw from her lounge; when Timi joins the link it’s clear to see the two writers have a beautiful relationship.

What was the motivation behind the book?

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff: The motivations in the project were born out of two things. Firstly, a personal sense of always wanting to look for joy even if it is sometimes really hard and also, being really interested in discussing topics around race and identity. Secondly and probably most importantly, out of the multitude of difficult and painful incidents and conversations that we were having in the summer of 2020 about Black Lives Matter around the world. I think there has obviously been a lot of discussion within the cultural space about things that have come out from that moment. I think you have to be careful about positioning any work of art around something that is traumatic and not using it as some kind of 'I did this because of that' because obviously, it is a lot deeper than that.

(Left) Charlie and (Right) Timi

How has it been working together?

Timi Sotire: Charlie is great. She clearly knows what she is doing and except for her being an excellent writer and editor, I think she is very approachable and really nice. So I literally felt like she was behind my back like 'Make sure you do this', she was really supportive and so was Penguin. The team was really, really nice. So yeah, we had a really nice experience.

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff: It has been joyful, and I definitely feel like I have gained a close friend in the process which is more than I could have hoped for.

What is one thing you can say you have learned about blackness that has been a part of yourself but you were not aware of until you were a part of the Black Joy project?

Timi Sotire: For me, as a Black person, things that bring me joy are black joy, which sounds very obvious but I think when it comes to this project I think I kind of expected to write an essay that was very typical about like my love for Jollof rice or black music but talking about One Direction (which I was nervous about) thinking people wouldn’t understand, but I think I’ve realized that thing that I thought made me a bit different is actually a big part of my blackness. A lot of people can relate to it. A thing that I have realized now is that black joy is whatever it means to you. It is a very individual thing, if you are a black person and there is something that brings you joy, that is black joy.

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff: It is interesting because I was going to say something that is not the opposite, but a take on that is a different lens. I completely agree with Timi, I think everyone’s experience of black joy is unique, it is embedded inherently in our uniqueness, but I was also reminded through doing this, I am thinking of Ribi’s essay about how many of my experiences growing up in this are not unique as well. You know, there are people who get it and can relate to it and it makes me feel a whole lot less alone. And then there are little things within that joyfulness that can’t be recreated in someone’s experience I am thinking like carrying the T-shirts with her, there are those little things. But more broadly I am thinking how held I can be and allow myself to be in the communities, black joy has been special.

You guys are speaking a lot about relatability and individuality. A lot of the writers talk about their childhood and their memories, as a multi-dimensional black person, would you say different versions of yourself from different walks of your life would accept who you have become now? What would they say about you?

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff: I think my inner child is happy for me. I do not have anything necessarily deep to say dramatically, but in terms of perspectives around like publishing books and like working with lots of different people, I hope all of that will make a little bit of good and that is more than I could ever ask for from the project, or in life rather, I think my inner child would be thrilled.

Timi Sotire: My inner child would be ecstatic. She would be really happy. Like, similar to what Charlie was saying, when I was younger it was a dream of mine to have my name on a book, so the fact that is happening I think my inner child would clap. My essay is about me as a tween, I think my inner child would be happy that I have reached a point where I can look back on those things fondly and feel right publicly about them because there was a bit of time where I was embarrassed about having these interests and having these weird things that make me happy. So, I think my inner child would be really glad that I am at a place where I can just be confident and unashamed of that.

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff: Yeah. I love that, and I think that is such a good point. What I often find is that when I write something down I am not necessarily at the stage where I am fully not embarrassed about publishing it and people being like ‘I feel it too’ or not even that necessarily, just like having it out there and rereading my own words, I get to be like ‘oh it feels good to be honest about who I am or about my interest, even in the past when I wrote about sex or stuff like that. It has been a process, I am glad you got to experience that too Timi, that is really cool.

Would you say most black people lay black trauma in the middle of every black story because blackness and death have been so inseparable?

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff: I think the conversation around black trauma within popular media is interesting. I think that there is certainly more awareness that blackness does not always give license to tell stories that are couched within that framework. Even in discussions like people just having interests in these stories and the importance of them being told more generally. I think the place that I fall on this is that I do not think there should be fewer stories on black trauma but, just more around black joy or balance the scales. That is obviously a simplistic way of looking at it and I am sure if you were to look into it the way academics would, they have richer things to say on the subject.

Timi Sotire: Yeah. I don’t want to say we are conditioned, but there is that agency. I feel like we are used to the idea of talking about our race and relating it to trauma. As Charlie said, I did mention it in my foreword that growing up in Britain I kind of thought that I had to struggle or go through something in order to experience joy. My parents even raised me to almost be accustomed to the struggle or discomfort, which I don’t blame them, but in doing so it made me used to the idea of battling through life and if I’d experience the joy I would almost feel guilty. One thing I love about this book is the fact that it does balance the scales a little and their stories are just happy and it is really nice. I really, really like that, I read the essays and I felt good and that was it and we do not want to take away from discussions surrounding racial trauma because I think they are important, it would be naïve and stupid of us to act like they do not exist in our lives.

What is the most common misconception around your intersectional identity (To name a few, women of color with an immigrant lineage), when you are in interracial groups or institutions?

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff: I think firstly the idea that I often get in journalism spaces is that I am automatically an expert in topics I perhaps know nothing about. That can be really hard to navigate, especially when you are in your early career trying to balance your ethics with the opportunities you are being offered. Growing up in Scotland, like a very white environment and people presuming that you can twerk, it sounds almost funny but like at that time it obviously was not. It was racialized and it went hand in hand with stuff that was darker than that. The stereotypes that people have when you walk into a room as a black or a mixed person will always be stereotyped in this country, which is where things like The Oreo come up.

Timi Sotire: The first thing I thought was that I have always tried not to internalize or unlearn that people will always question my intelligence for as long as I can remember. I think people always assumed that I am a bit of a dumb-dumb, like from teachers, from students, and colleagues at my old work. I think people would just assume and did not really know that much and I have never really known if that is because of my race or gender or both. It’s something that has been in my life for ages and I think it’s only been like in the past couple of years that it has been happening less. I was raised in Essex and it was a predominantly white space, I think people just made the assumptions of me not as being smart like those around me.

"I think everyone’s experience of black joy is unique, it is embedded inherently in our uniqueness"

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff: And actually, you are so smart and they were all wrong.

Charlie, you mentioned in your foreword that you do not believe there is yet a substantial body of work on Black joy in the same way there is about Black trauma. What do you think is the easiest way that can echo Black Joy more, as a political reaction to the world?

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff: Let me just read that back because I am always changing my mind about things. I think if I were to reword this slightly, I would say there is a sense of a body of work on Black Joy that has been articulated as such. It is not that black people have not been making things that are joyful for centuries or however long. It is just not necessarily being named as such. We are one bigger piece of a network.

Timi this one is for you. You mentioned in your essay that your skin did not matter online being a One Direction fan with all the other girls that did not even look like you. You said you felt at home. Would you say the internet is a safety net for black people that sometimes feel unaccepted in communities dominated by people that are not like them in real life? Do you think it is a positive evolution?

Timi Sotire: That is a good question. I would say that the internet can be a safe space in some instances, but I think it solely exists as a safe space. I think as black people we need to be aware that biases and hierarchies that exist in the outside world will be transferred into the internet because the internet does not exist in isolation. So it is inevitably going to be influenced by the offline world. I also think that… (now that I think about it, I could have put it in the essay) the internet has definitely developed a lot, as social media has in the past ten years. The Twitter I was on, is definitely not the Twitter now because I think there is definitely less of like a boundary between the online and offline world. I feel like I benefited from being on social media in that area where like it was just fun and new, I could talk with people and make friends. I was like in a space where for me, in my life, it helped me and allowed me to feel safe while I was home but I realized that wasn’t the case for everyone at that time as in the case for some people right now. It is different, it depends on every individual person. I’d say that as black people we have the power to carve out our own safe spaces online and offline, but I do not think we should be naïve and ashamed because the internet in theory can be anonymized and allows you to say whatever you want. That is solely a safe space. As with most things, you can make your own safe space.